Latex sacs in pen are nothing new. The introduction of the latex sac to hold the ink was however, a radical idea when it was introduced a hundred years ago. (shocking how time flies!) Radical enough that the “eyedropper” or “safety only” crowd was left scrambling to catch up, and the patent battles that developed were as common as they are today between Samsung and Apple.

The problem is, that wonderful idea had a built in flaw in that the sac starts to break down, heading for the inevitable failure the first time the pen is filled. It was true back then, and is true a century later. That flaw spawned a lot of research into alternatives and better materials. Piston fillers, plunger fillers, aerometric fillers, and eventually the piston converter were all ways to get around the problem of a sac. But they came with their own set of problems. The development of Parker’s “plyglass” sac (really PVC) was a biggie, and one of the reasons for the popularity of, and long life of, the Parker 51. I’ve had Esterbrook pens with project numbers stamped on them. The source was from the estate of a man who was a chemical engineer for Esterbrook. The only thing that I can think of is that these pens were being put in to real world use to test something, and I think that they were testing rubber compounds for their sacs. Esterbrooks sacs are the toughest that I’ve seen in any pen. I often find the pens with the original sac in the pen, many times still in fine shape though the rest of the pen shows evidence of serious use!

Fast forward to today. The legacy of the latex sac lives on, and it’s disposition to fail, simply leaking, turning to goo and eventually becoming petrified is one of the reasons why I’m in business. They fail. Some sooner than others, but they eventually fail.

Those of us who repair pens for a living have seen a startling, indeed perhaps alarming, trend of premature failures in pens sacs happening at an increasing rate over the last 5 or 6 years. There’s a lot of discussion about the cause, but it often comes back to one of two things – the material used to make the sac, and the ink used in the pen. When I dig and ask questions about how the pen was used, I find that one of the modern super-saturated “boutique inks” like Noodlers or Private Reserve, or a saturated ink containing red die was used in the pen. Failure sometimes happens in a matter of a couple of months, sometimes it takes several months or a year.

This is very frustrating for a professional pen mechanic. We can do everything possible to make a pen write very well, as it should. We buy the best materials we can to restore the pen, only to see the sac fail in a few months instead of several years later as had been the case a decade ago. The most likely causes are the things over which we have absolutely no control – the material used to make the sac, and the ink that the owner chooses to use in their pen.

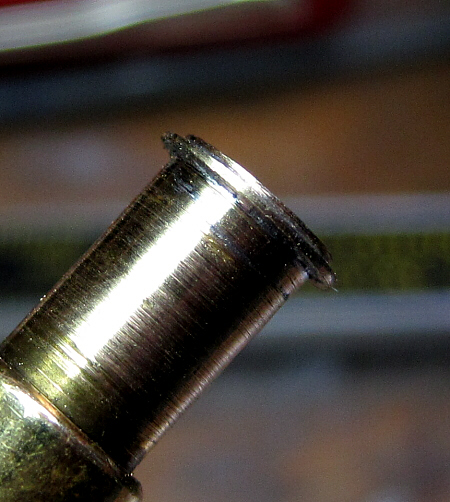

So one asks, why don’t you just use one of the synthetic sacs? The sacs from north of the border were sold as “silicone” and work very well. I’ve used them for years. But some testing in the last year or so revealed that the sacs currently in production are not silicone, but PVC. “So what?” you say. They used PVC sacs in Parker 51s for years without any problems. Well, almost no problems. We see a fair number of aerometric 51s with sac nipples that are soft…. soft enough that they can fail and tear. The reason? The plasticizer leaches out of the PVC and softens the celluloid of the sac nipple. Once it turns soft, it can not be reversed. The same thing can happen to a celluloid PEN. The PVC sac in a Duofold Sr. could soften the barrel from the inside out, and once soft it can not be reversed. It would take a long time, and we might not notice, but it would happen. The difference with a 51, or a PVC sac in say a Sheaffer snorkel, is that the sac never comes in contact with the barrel because of the metal sac guard.

So a true silicone sac was developed. The theory being that they are more or less inert, like the PVC are not degraded by contact with ink, and will not release the plasticizer that can have a negative impact on some plastics. Cool. Except that they come with their own set of issues. Silicone doesn’t stick to anything but silicone. So you have to use a silicone RTV adhesive, and a particular kind that will not release acetic acid as it cures. And that non corrosive RTV (room temperature vulcanization) should be a type that releases an alcohol VS a ketone.

There was great joy in the shops of pen mechanics because even though you had to use a special adhesive that takes longer to set and therefore slows you down, maybe, just maybe we finally had a sac material that would provide the long life and resistance to damage from modern inks that we desire.

But then we found out about the gas permeability issues of silicone sacs. The short form here is that the silicone sac allows some gasses to pass through the wall of the sac. In other words, to some gasses but not the ink, the walls of the sac are porous. That means that the controlled leak of the fountain pen may not be quite so controlled. If a pen is stored on it’s side rather than nib up, you could end up with an oozing pen or in the worst cases, a cap full of ink. I’ve heard of cases where this has happened, but I also have them in several pens, and have had clients testing and watching for oozing without having it happen.

So what should a pen mechanic do? I still use latex sacs, because they work best in most applications. They stick better to the sac nipple than PVC or silicone, they fill well, and they are less likely to tear. They’re the only option for Parker Vacumatic filled pens. But they are not the best thing to use in a Sheaffer snorkel. Sac failure usually results in ink in the barrel, and if not corrected in time it means a rusted spring, screw, and in really bad cases damaged sac guards and Touchdown tubes.

Some folks really want their saturated inks, no matter what. Snorkels demand a synthetic sac to prevent damage to the internal parts, and they’re a good idea on PFM and Touchdown pens too. But both synthetic sac materials as we have noted have issues.

In general then, if you want to use a synthetic sac so that you can use you boutique ink, use a PVC sac in a hard rubber pen or a pen with a sac guard that keeps the sac from contacting the inside of the plastic barrel wall. But I think that the silicone sac is the better material in most applications as long as you are willing to accept the possibility (not probability) of oozing.

Every option has it’s trade offs. There are no silver bullets.