My Parker 51 doesn’t hold any ink!!

Monday, October 31st, 2011Every so often a thread pops up on FPN, or I receive an email from a client saying that their Parker 51 doesn’t seem to be pulling in any ink. “I fill it, and it seems to be OK, but I only get two or three drops out of the pen.” Now there are occasions where something really is wrong with the pen, maybe the breather tube is damaged or missing, but often there is not. The pen is filling just fine, it writes fine, but their understanding of how a 51 works is, well, lacking.

The Parker 51 is one of the best pens ever made. Steady, tough, reliable, it’s rare for one to flood unless it’s filled wrong. It’s designed to take in a maximum amount of ink, which can take several strokes of the filler.

To be able to do this and not push the ink back out on each stroke the 51, like the Vacumatic, uses a breather tube. With each stroke of the filler pump, or squeeze of the pressure bar, air is pushed out the breather tube which is larger in diameter than the slit in the feed. When the filler is released, ink is drawn up the breather tube, and it flows over the top into the barrel. Each time the filler is pressed or squeezed, more air is pushed out the breather tube but the path back out for the ink is restricted. The process is repeated until the level of the ink reaches the top of the tube. No more ink can be drawn into the pen because it’s pushed back out of the breather tube with each pump.

Add to the filling process the collector in a 51. Under the hood is a collector that has what seems like a gazillion little fins. These fins catch any extra ink that comes down the feed, keeping the pen from flooding as you write, or the ink expands in the barrel from either body heat or changes in air pressure. It’s all designed to keep the ink in the pen unless it comes down the feed to the tip of the nib as it’s supposed to – and it works very well thank you!

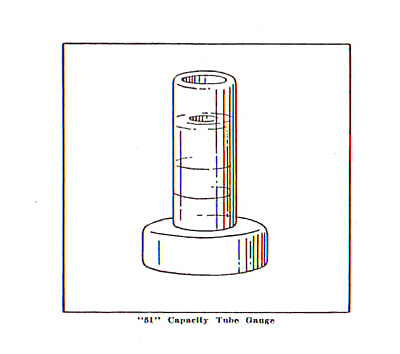

You can see why measuring how much ink comes back out of a pen after it’s filled can lead to the impression that the pen is not working right. You don’t get much back out, and you’re not supposed to. Parker recognized this, and gave dealers a way to demonstrate that the pen was indeed filling as it should. This illustration appears in the 1946 Parker service manual. It’s described as a tube to “test the capacity of Parker 51 pens.

A repairman or dealer would fill the tube to the top line with water, then fill the pen cycling the pump 10 times, pulling the pen out of the tube on the 10th stroke. If the water or ink had dropped down to the level of the second line, the pen was working properly. The manual also suggests that it’s a good way to demonstrate how to properly fill the pen.

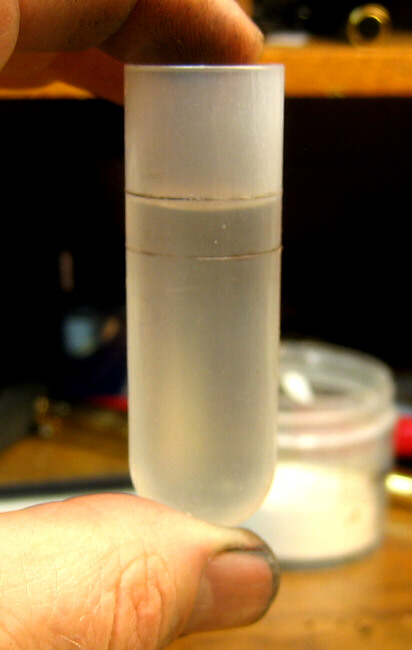

When I read the manual, I realized that I need a similar way to test 51s, so I made my own testing tube. As a matter of fact, I made a couple of them so that I could always find one. It’s proven to be very handy in testing a 51 both before it goes out, and if one comes in for a warranty repair.

You can make one yourself. Any tube that’s about the same diameter will work. My 51 tester is made from a paint ball tube. The tube is about 0.700″ in diameter, and the marks about 0.300 inches apart. I fill to the top line, and if the the level of the liquid drops to or close to the lower line, the pen is working as it should. The volume is about 1.6 – 2 CC if liquid. The Vacumatic and aerometric 51 pens hold about the same amount of ink.